Can we improve security risk assessments by understanding why people commit crime? Part Five.

Part five: Conjunction of Criminal Opportunity

Hi friends,

This is the final post of this series. But, in the next few weeks, my friend, Musaab, will be writing a guest post.

You don’t want to miss this.

It’s well written. Covers the best of theory and practice. And, it’s deeply insightful.

Over the past few weeks, we’ve looked at:

classicism: people are rational, operate on the basis of pain and reward, and commit crime if the reward is greater than the pain.

positivism: people commit crimes for biological, psychological, or sociological reasons.

left realism vs right realism: people commit crimes for many reasons, including those identified in both the classicist and positivist approaches. But, as realists, crime prevention must be approached pragmatically.

situational crime prevention: people commit crime because there is an opportunity to do so.

So what?

The theories that we’ve looked at to date are really helpful for understanding not only the causes of crime, but also how we can control crime.

But I know what you’re all thinking. So what?

So what if people commit crime because they’re predisposed?

So what if people commit crime because they’re hedonistic and simply choose to?

So what if the environment creates the opportunity to commit crime?

So what does it mean to me, a security professional, if all of these are true to some extent? How does that knowledge help me reduce crime? Protect my friends, colleagues, and family? Protect my information? Ensure my organization can still function?

Well, now you’re armed with a series of approaches to tackle what keeps you up at night.

But I know that at this point, things are still abstract. So, I wanted to provide you with a final tool. An actual tool. Well, actually, it’s a game. A serious game.

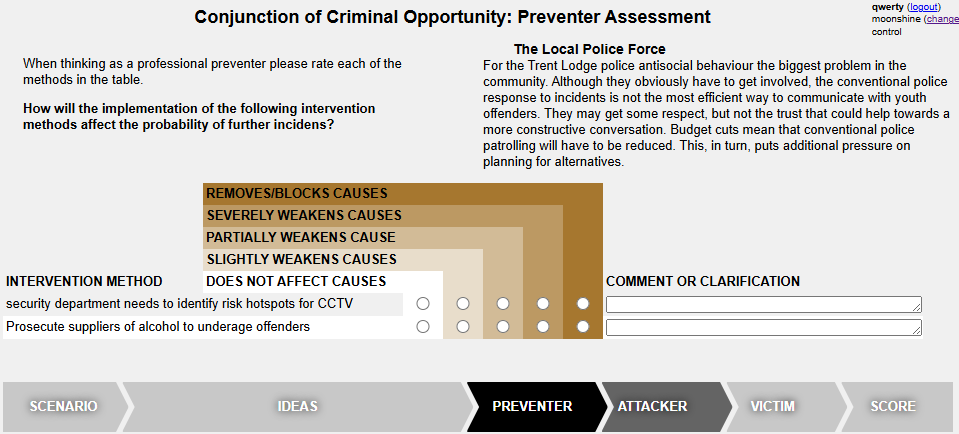

It’s called the Conjunction of Criminal Opportunity (CCO). In a moment, I’ll share the link. But first, let me tell you a bit about it.

The CCO was developed by a friend of mine at the UK Home Office. A brilliant researcher, named Paul Ekblom.

He recognized that regardless of dispositional theories (positivism, for example), crime happens when a likely offender + suitable target converge in time and space in the absence of a capable guardian. He summarizes the CCO like this:

A criminal event happens when a predisposed, motivated, and equipped offender encounters, seeks, or engineers a situation conducive to crime, perceives opportunity and decides, or is provoked, to act. The situation comprises a human, material or informational target that is vulnerable, attractive, or provocative, perhaps within an insecure enclosure, and in any case located in a wider environment that motivates and/or gives tactical advantage to the offender, who may also be aided deliberately, recklessly, or innocently by people acting as crime promoters, and insufficiently hindered by people acting as crime preventers.1

If you caught last week’s post on situational crime prevention, this should sound very familiar to you. It is essentially an expansion of the routine activity approach.

Now, enough reading.

It’s time to play.

CCO Serious Game: https://cco.works/

When you click on the link, there will be a video that walks you through how to play. Then, you will be given a few scenarios related to information security, but also a real-life example from the UK on juvenile delinquents. In that case, Paul Ekblom used SCP to redesign the environment to reduce crime and indeed watched crime go down.

That’s the scenario that I chose.

How to use CCO in the real world.

Assuming you just played the CCO game, you may be asking how you can use that in the real world.

First, use the theories that we’ve discussed to understand what properties of the attacker and the situation are creating opportunities for a crime to happen.

For example, a broken shop door combined with a minor that comes from a sad family situation may be inclined to steal. Maybe. But don’t stop there.

Second, think about what interventions you can implement and link them to the appropriate cause:

For example, can you fix the door? Or, are you in a position to use educational or parental programs to help families in need prior to the criminal event? For example, organizations like Safe Families Canada have a wonderful program aimed at helping young families in need, before the family breaks down.

Third, understand that the world is a complex adaptive system made up of a bunch of complex adaptive systems (CAS). So, let’s be real. You can’t fit interventions into causes in a neat and tidy fashion. CAS’ are non-linear and there is no telling what ripple effects a single intervention may have across the opportunity spectrum. So, identify the adjacent influences.

Fourth, think like a defender. Will your plan weaken the causes of crime?

Fifth, think like an attacker. Will the intervention stop you from committing the crime?

Sixth, put your feet into the shoes of the victim. How will the proposed interventions reduce the harm of future incidents?

Finally, tally up your score.

In closing,

The CCO may take some time getting used to. But it is perhaps the most valuable tool that I have come across that merges theory and practice together in support of reducing crime.

I hope you try it.

And, I hope you’ve enjoyed this little blog series on the causes of crime and how we can control it in the future.

My very best,

Shawn

Ekblom, P. (2011) Crime Prevention, Security and Community Safety Using the 5Is Framework, New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 136.